Although reverse mortgages have long had a bad reputation with financial planners and the public, new government rules and research articles from the past few years are causing many to take a second look at their potential role and value.

Research published in the Journal starting with the Barry Sacks and Stephen Sacks article, “Reversing the Conventional Wisdom: Using Home Equity to Supplement Retirement Income,” from the February 2012 issue, reaches an important conclusion that there is potentially great value in beginning a reverse mortgage as soon as eligible (age 62) for those with a reasonable expectation to remain in their homes. The idea is to begin the reverse mortgage early, even if proceeds from it may not be taken out for many years.

The reason for these conclusions relates to how the line of credit on a reverse mortgage grows throughout retirement. Understanding this detail is probably one of the most challenging aspects when first learning about reverse mortgages as a retirement income planning tool. This column seeks to provide greater understanding for how this process works.

Naturally, the loan balance on a reverse mortgage grows over time. For the most typical type of HECM reverse mortgage, it grows at a variable rate reflected as the one-month LIBOR rate, plus a fixed lender’s margin set in the contract, and a fixed mortgage insurance premium of 1.25 percent. This combination of three factors is called the effective rate.

More broadly, the effective rate is applied to growth not just for the loan balance, but also for the overall principal limit. This may sound technical, but to grasp the arguments about the value of opening a line of credit as early as possible, it is an important point to understand.

Except for rare past cases in which a reverse mortgage included a servicing set-aside that grew at a different rate than everything else, the principal limit, loan balance, set-asides, and remaining line of credit all grow at the same effective rate. This will be true for all new loans today, because changes have been made so that any new set-asides will also grow at the same effective rate.

In other words, the unused line of credit grows at the same rate as the loan balance. Really, it is the overall principal limit of the reverse mortgage that grows at the effective rate. Again, this principal limit is the sum of the loan balance, the remaining line of credit, and any set-asides:

Principal Limit = Line of Credit + Loan Balance + Set-Asides

These factors all grow at the same effective rate, which will expand the size of the overall pie over time, which can be carved up in any desired way.

The next important point is that interest and insurance premiums are charged on the loan balance, but not on the set-asides or line of credit. To be clear, set-asides are not part of the loan balance until actually used, but they limit access to the line of credit. Though interest and insurance premiums are not levied on set-asides or the line of credit, both of these components grow as if these costs had been charged, as they are components in the effective rate.

When funds are borrowed, the line of credit decreases and the loan balance increases. Conversely, voluntary repayments increase the amount of the line of credit, which will then continue to grow at the effective rate, allowing for access to more line of credit later on.

I believe that the motivation for the government’s design of the HECM reverse mortgage program is based on an underlying assumption that borrowers would spend from their line of credit sooner rather than later. Implicitly, the growth in the principal limit would then reflect growth of the loan balance more so than the growth of the line of credit. In other words, designers assumed the loan balance would be a large percentage of the principal limit. The line of credit happens to grow at the same rate as the loan balance, and if left unused, the line of credit could grow to be quite large. There was probably not much expectation that individuals would open lines of credit and then leave them alone for long periods of time. However, the brunt of the research on this matter published in outlets such as the Journal since 2012 suggest that this sort of delayed gradual use of the line of credit can be extremely helpful in prolonging the longevity of a retiree’s investment portfolio.

Consider two different individuals who each open a reverse mortgage with a principal limit of $100,000. To simplify, assume that 10 years later the principal limit for both borrowers has grown to $200,000. Person A takes out the entire $100,000 initially from the reverse mortgage. For Person A, the $200,000 principal limit after 10 years reflects a $200,000 loan balance, which consists of the initial $100,000 they received plus another $100,000 divided between accumulated interest payments and insurance premiums.

However, Person B opens the reverse mortgage but does not use any of the credit, so that the $200,000 principal limit at the end of 10 years fully reflects the value of the line of credit. This value was calculated with an implicit assumption that interest and insurance payments have been accruing, even though they haven’t. Person B can then take out the full $200,000 after 10 years, and then Person B has the same loan balance as Person A, but Person B has received $200,000 rather than $100,000. Person B bypassed accumulating the interest and insurance, to the obvious detriment of the lender and the mortgage insurance fund.

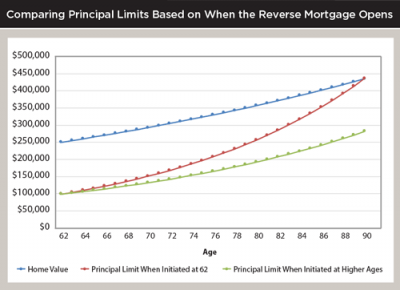

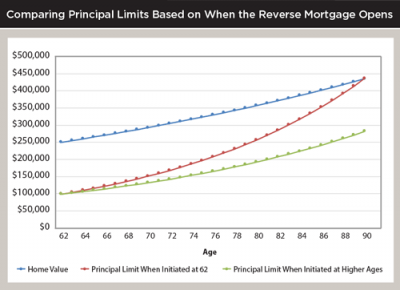

Would the line of credit ultimately be larger when it is opened early on, rather than waiting until later to open it? We can further explore this question with a more realistic type of example. The graph provides an illustration of the impact of opening the reverse mortgage at different points of time using a few basic assumptions. For simplicity, I assumed that the one-month LIBOR rate stays permanently at 0.2 percent, and the 10-year LIBOR swap rate remains permanently at 2 percent. The lender’s margin was assumed to be 4 percent, and home inflation was 2 percent.

For a 62-year-old with a home worth $250,000 today, the figure charts three values over time until the individual is 90. The home value grows by 2 percent annually, and it is worth $435,256 by age 90. The principal limit for a reverse mortgage opened at 62 is $98,750 (based on a principal limit factor, or PLF, of 39.5 percent for the 6 percent expected rate used in this calculation). The effective rate that the principal limit grows is 5.45 percent, and the principal limit is worth $436,357 by age 90. At 90, the principal limit has actually exceeded the value of the home. As a side note, if this principal limit were reflected as a loan balance instead of a line credit, the loan is non-recourse and the amount due by the borrower cannot exceed the home’s value—this is a guarantee supported by the insurance premiums.

The graph also shows the available principal limit if the reverse mortgage is not opened until each subsequent age, rather than at age 62. By delaying the start of the reverse mortgage and assuming the expected rate of 6 percent remains, the principal limit grows because the principal limit factor is higher at advanced ages, and because this factor is applied to a higher home value. Nonetheless, even at age 90, the available principal limit for a new reverse mortgage is only $286,046, which is based on a PLF of 64.8 percent applied to a higher home value.

The message from this example is that opening the line of credit early allows for a much greater availability of future credit relative to what could be obtained by waiting to open the reverse mortgage later in retirement.

This example has assumed that interest rates remain low, but if interest rates were to increase in the future, the value of opening the line of credit today would be even greater. With lower rates today, the available PLF is currently higher. Then, higher future interest rates would cause the effective rate to be higher, so that the principal limit grows more quickly.

Rising rates would also increase to the expected rate used to calculate principal limits on new reverse mortgages in the future. This would reduce the principal limit on newly issued future loans. Only extreme growth in home prices could possibly allow more credit to be obtained by delaying the start of a reverse mortgage, but higher home price growth would surely be caused by higher inflation, which would also increase interest rates and reduce the future PLF. It seems to be a relative certainty that more credit will be available in the future by starting the reverse mortgage as soon as possible rather than by waiting to open it later.

All of this may sound too good to be true, and it probably is, to some extent. Perhaps this is a reason why it is difficult to grasp this concept of line of credit growth throughout retirement. I’ve already noted that unused lines of credit work for borrowers to the detriment of the lenders and the government insurance fund. This use of a reverse mortgage does still exist today and would be contractually protected for those who initiate reverse mortgages under the current rules. But at some point, I expect to see new limitations about line of credit growth, especially as more people start to follow the findings of the recent research on this matter.

Line-of-credit growth may be viewed like an unintended loophole that is strengthened by our low interest rate environment. The rules will probably be changed someday for newly issued loans. Until then, research points to this aspect of reverse mortgages as a valuable way they can contribute to a retirement income plan.

Read more about Wade Pfau’s latest research on reverse mortgages in the April 2016 issue of the Journal. His peer-reviewed research paper, “Incorporating Home Equity into a Retirement Income Strategy” will explore how the strategic use of a

reverse mortgage could improve retirement outcomes.